Writing a parser for CS:GO files

A good friend of mine just recently got into game hacking. More specifically into CS:GO hacking. During that process he came across a certain file he needed to parse. The file looked very similar to json, but it was no json. Have a look:

"items_game"

{

"game_info"

{

"first_valid_class" "2"

"last_valid_class" "3"

"first_valid_item_slot" "0"

"last_valid_item_slot" "54"

"num_item_presets" "4"

}

"rarities"

{

"default"

{

"value" "0"

"loc_key" "Rarity_Default"

"loc_key_weapon" "Rarity_Default_Weapon"

"loc_key_character" "Rarity_Default_Character"

"color" "desc_default"

"drop_sound" "EndMatch.ItemRevealRarityCommon"

}

...

}

...

}

And yes, before you ask, there are already some parsers for that file format out there. But most of them either work very hacky or are quite unreliable. Some of them even use Regex to parse those files, which you should never ever do, but we’ll get to that later!

After said friend told me about the challenge I thought it could be a funny challenge and I wanted to help out. So given these circumstances, I decided to build my own parser for those files.

One sidenote right at the start: The content in this blog post might be shrinked a lot because I did not want to write a boring long text, so if you are new to this and don’t understand all the things, no worries - the problem is not you. Also I might reduce statements to their core which also means that stuff might not be as accurate as it could be. If you know better, please don’t kill me, this article is not meant for parser developers.

Theoretical background

In order to build your own parser you need a bit of background knowledge. I am trying to make this short, because you can use 2 full years in university studying that stuff. During my computer science studies I had a lecture called something like “compiler design”, in which we learned how compilers work and how to build one. Back then I did not like that lecture because it was very dry and very theoretical, but now I picked up the interest because there are practical use cases to use it for. For everyone not knowing what a compiler is: Simply said it’s the tool (or a collection of tools) which creates an executable program out of your source code. And one of the first steps of a compiler is to read the file (where the code resides in) and parse it. Now how does it do that?

Grammar

You cannot parse anything if you don’t know which rules your language (file, source code, etc.) is following. The grammar, which literally means the same for spoken languages and programming languages, defines the order in which certain words or rather “tokens” are allowed in. The other way around you can say that a grammar produces a language. Using the rules of the grammar you can create sentences of the language that grammar describes.

Here is a very easy example code written in Python:

if value == 3:

print("Value is 3")

Using this example, we can see that Python has certain syntax rules. We can list some of them in natural language, such as:

- The context for the if-clause must be indented 4 spaces (or 1 tab).

- After the keyword

printthere must be two parentheses,(and), which surround an expression (string, list, object, variable, etc.) - In the condition of our if-clause there must be any kind of expression or variable to check on. In our case it’s a comparison (

value == 3) - …

Those examples above are only a very small set of informal rules which define how python programs must be built. If you break some of those rules, the python interpreter/compiler will tell you that it can’t understand what you have written. That’s when you get syntax errors. Take the following code for example. We put an assignment into the condition and the python compiler tells us that it does not know how to interpret this line of code.

if value = 3:

File "<stdin>", line 1

if value = 3:

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Types of grammars

You might or might not have heard of it - there are different types of grammars. And that’s also the reason why you CAN’T and SHOULDN’T (and imho MUSTN’T 😄) parse HTML or JSON with RegEx. The different types of grammar are described in the Chomsky hierarchy. It contains 4 different types of grammars. They are labeled type-0 to type-3 where type-3 is the “least complex” and type-0 is the “most complex” one. A type-0 grammar contains all the grammars described by type 1, 2, and 3. A type-1 grammar contains all the grammars described by type 2 and 3. And so on.

Type-0 grammar is called “recursively enumerable”, type-1 grammar is called “context-sensitive”, type-2 grammar is called “context-free” and type-3 grammar is called “regular”. And as that name might already have spoilered… you can only parse type-3 grammar with Regular Expressions. As I already wrote twice: that’s the reason you can’t parse HTML/JSON with it, because those languages use type-2 grammars. If that still does not convince you, check out this legendary stackoverflow answer, it’s really worth it.

(E)BNF

To describe a grammar, we can use the (extended) Backus-Naur form or for short “EBNF”. EBNF is somewhat of a description language for grammar. It consists of “terminal symbols” which are literal characters, “nonterminal symbols” which can be seen as “variables”, and “production rules” with which you can “produce” data allowed/accepted by the grammar. But apart from producing data you can also verify the grammar of a language with production rules. And to throw that in right at the start: Yes (e)BNF is used broadly. I would say that you find it in any language/grammar description documentation. For example in the Python Language Reference documentation.

A very simple set of EBNF rules could be:

digit_excluding_zero = "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9" ;

digit = "0" | digit_excluding_zero ;

natural_number = digit_excluding_zero, { digit } ;

We can now replace any nonterminal (such as “digit_excluding_zero”) with the content of its definition. It’s similar to the concept of variables in programming languages.

As you can see, digit_excluding_zero can contain any one digit from 1 to 9, because the | means “or”. digit can contain any one digit from 0 to 9. natural_number can contain any non-zero digit in the beginning and any amount of any digit (including zero) following. That’s because of the curly braces - they mean something like “this token can repeatet 0, 1 or unlimited times”. The example above was taken from the EBNF Wikipedia page.

So that’s basically how we describe our grammar. EBNF is not really complex, but I could write about it for hours, and to prevent me from doing so, I am going to cut short here. Go to the wikipedia page if you feel the need to read up on it.

Building your own parser

Well this heading doesn’t fit a hundred percent to what comes next. I was not actually building a whole parser myself. Why? Because it takes quite some work to build a custom parser yourself all from scratch. That’s why I used LARK which is a parser/parser generator. It takes a grammar written in a language very similar to EBNF and creates a parser that matches that exact grammar. Is that “cheating”? It might look like that but it’s absolutely not. Even professionals use parser generators.

First and foremost we import certain predefined nonterminals and set the policy to import all whitespace characters, which makes it easier for us to parse the file later on, since we can ignore all whitespaces.

%import common.ESCAPED_STRING

%import common.WS

%ignore WS

Now we can start defining first terminals and nonterminals. First we define the file as a list of objects. Then we define the object as a string, followed by a curly brace, followed by an optional value, followed by a closing curly brace.

We also define a pair as two strings and we define a list as a listitem followed by any number of list items.

A listitem can be an object or a pair.

And last but not least - value can be anything of object, pair, list, or ESCAPED_STRING.

file : object [object*]

value: object

| pair

| list

| ESCAPED_STRING

listitem : object

| pair

object : ESCAPED_STRING "{" [value] "}"

pair : ESCAPED_STRING ESCAPED_STRING

list : listitem [listitem*]

%import common.ESCAPED_STRING

%import common.WS

%ignore WS

That describes our syntax pretty well. There is only a very small issue: The grammar is not parsible by a “Look-Ahead LR parser” (LALR parser). You may ask “wtf is a LALR parser” and “why can’t it parse the file given our grammar?” and both are adequate questions. I could give you an answer, but for that we need to go deeper into parsing. Especially into the parser stack and shift/reduce conflicts. Please bear with me - a very very short digression. This topic is not easy and you might want to check some tutorial or other literature on the topic if you are trying to understand everything. If you just care about the result and the code, you can jump down to the bottom of the post.

How parsers work - short digression

(Bottom-up) Parsers use a stack to store the tokens they parse. Putting tokens on that stack is called “shifting”. After a parser parsed some tokens and any production rule matches on the tokens on the stack, it “merge”s those tokens together. In our example the parser can merge together two ESCAPED_STRINGs such as "first_valid_class" "2" and replace those with the nonterminal pair because of our production rule pair : ESCAPED_STRING ESCAPED_STRING. That process is called “reducing”.

expr: number

fac: number + !

In this example (taken from here) given the input number! we can either reduce directly after parsing a number and have an expr and an !, or we can shift the ! as well and reduce it together into fac. The first grammar we developed is no LR-grammar because for a parser it’s ambiguous. Such as the situation I just described with the example above there are cases where some rules allow it to either shift or reduce and both results would make some sense in the first place. Some parsers can comprehend that ambiguity, such as the (very slow) “Earley parser”. It will be used as a default when using LARK. That parser takes about 50 seconds to parse the whole file. A bit too much in my opinion… so let’s try fix that.

So when the parser is in the situation where it could either shift another token onto the stack (because there is another rule that allows it) or it could reduce the items on the stack, then you call that a “shift/reduce conflict”, because there is no way for the parser to decide what to do. There are also “reduce/reduce conflicts” which means there are several rules a parser can reduce something to. That stuff might be a bit hard to comprehend at first glance, so no worries if you did not understand everything. The most important part is that we want to change our grammar so that we don’t have any conflicting rules that could lead us into conflicts. By the way, there are also reduce/reduce conflicts (when the parser has multiple possible rules on how to expand a nonterminal).

As we already know there are multiple types of grammars. But there are also multiple types of parsers. You can differentiate between top-down and bottom-up parsers. And that does not mean that they read the file from top-down or bottom-up. Their names describe the way they build the parse tree. Bottom-up parsers work from the bottom of the tree (smallest parsible element, literal/terminal) to the top of the tree (nonterminals, structures). Top-down parsers work from the top of the tree down to the bottom of the tree. That also means that bottom-up parsers are generally

Since our grammar is not a LALR(1) grammar, because (e.g.) an object can be reduced into a value or into a listitem. That means that our grammar is ambiguous for LALR Parsers.

LALR(1) Grammar

The LA in LALR means, that we are using a parser with Look Ahead functionality. That means that we check the following token before we make a final decision if we should shift or reduce. The LR means, that we are having a Left-to-right, Rightmost derivation in reverse parser. Rightmost means that we parse the input from the bottom up. That also means that if we’d parse mathematical terms such as a + b - c we would get the result a * (b - c). For top-down parsing it would look like (a * b) - c.

Since the parser uses a look ahead, we must make sure that there are no two production rules that produce the same outcome or are otherwise ambigious. Unfortunately currently we have value and listitem and file which can produce the same outcome (namely object). Now we need to change that - e.g. by adding other characters so that the parser knows exactly when to shift or reduce.

When we merge our rules a bit more together and clean up the order a bit, we get the following grammar:

?value: list

?listitem : object

| pair

string : ESCAPED_STRING

object : string "{" [value] "}"

pair : string string

list : listitem [listitem*]

%import common.ESCAPED_STRING

%import common.WS

%ignore WS

This works pretty well so far. No shift/reduce conflicts, because with a lookahead of 1 every rule is defined in an unambiguous way. Also no reduce/reduce conflicts. Also don’t mind the ? for now. They are LARK internal marks on how the abstract syntax tree built by the parser will look like. The whole parsing process only took 4 seconds. That’s an insane improvement in speed compared to the 50s it took before.

Result

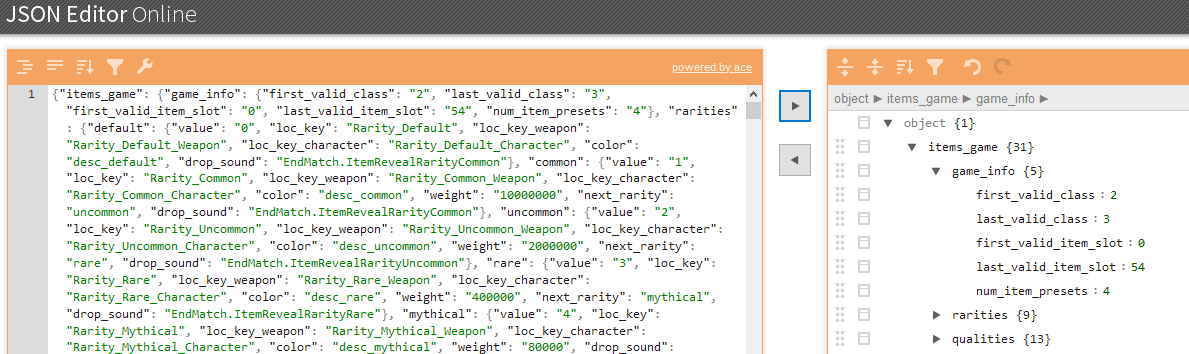

Now when we parse the file, LARK will generate an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) for us. That tree contains the whole file with the parsed tokens as leaves in a certain order. Depending on the type of parser your AST will look different. Based on that AST we can transform the data into any format we want to. I decided to write my own Transformer class called TreeToJson, which extends the LARK Transformer class, which is used to transform an AST into a custom data format. But if you know how the AST data structure looks like, you can use your own implementation to do anything with that data.

After transforming the data inside the AST we got a useful data format. We can use that to e.g. create json out of it. But it’s not limited to json, we can basically create any data format, since we can define the data structure now.

And yea, that was the result. The python script with the LALR parser ran about 4-5 seconds and printed nice, JSON-formatted data which can be used to further work with it.

If you want to play around with the parser and stuff, I created a GitHub Gist for this very small project. Feel free to check it out: https://gist.github.com/d-Rickyy-b/ce6edfd12788b821839305eaeb5b18ac

Since this topic is quite hard to understand, please don’t worry if you did not get everything. I’ll be glad to help you out on your questions. Feel free to contact me. Also make sure to leave me comments and annotations on this blog post!