rexamine - Lightweight Regex Stream Matcher

My first contact with the Go programming language was somewhere around 2018. Some months later, I gained interest in the language and started thinking about possible projects I could use Go for. Finally, in November 2020, I started working on my first Go project, and I immediately fell in love with the language.

I love the clean syntax, the static types, and the simplicity of usually rather complicated things such as multithreading.

In 2024, I worked on a small module that enables extracting matches via regex from a stream of data, named “rexamine”. This blog post explains the reasons and ideas behind the module I created.

Eventually, the package allows for memory efficient regex-scanning of data streams. In its default configuration, rexamine uses about 19 KB of memory and is about 5-7% slower than reading the files completely into memory and scanning through the RAM directly.

The Problem - Memory footprint

The year is 2023, and by that time I already had gathered quite some experience with Go. I started yet another unfinished side project™️ that involves scanning an arbitrary amount of files (of arbitrary size) with a certain regex to extract the found matches and process them later on. Usually, to do this, one could write some code like this.

myRegex := regexp.MustCompile(`test`)

// generate a list of all files within a root directory

files := findAllFiles(rootDir)

for path := range files {

scanFile(path)

}

// [...]

// scanFile returns a list of all matches for a given regex

func scanFile(path string) []string {

var results []string

// open the file for reading

file, err := os.Open(path)

// ...

// read the file's content into a buffer

buf, err := io.ReadAll(file)

// Alternatively:

// buf := &bytes.Buffer{}

// _, copyErr := io.Copy(buf, targetFile)

// ...

// run regex matcher over the buffer

matches := myRegex.FindAll(buf, -1)

for match := range matches {

results = append(results, string(match))

}

return results

}

There clearly is nothing inherently wrong about this code.

But I quickly noticed a major drawback.

The larger the file, the higher the memory consumption.

That happens, because the file is completely read into memory by using io.ReadAll(file) (or io.Copy() if you prefer that).

Yes, that is obvious - you might say. And of course it is. But you only start caring about these things once you suddenly need to handle files of sizes that either make up a significant portion of your RAM or even exceed its size.

How Go extends slices

Depending on how a file is processed, the used RAM might even exceed the file’s size by a lot.

This is partly due to the fact that slices are initialized with a certain capacity and extended as needed.

There are basically two ways how to read files: io.Copy and io.ReadAll.

io.Copy (when writing to a bytes.Buffer) always duplicates the slice’s capacity when writing new data to a full slice.

In the worst case, this means that we allocate 2x the size of the file.

Also when reslicing, a new slice is created via append() and the existing array is copied each time we run out of capacity.

Both leads to excessive RAM usage.

io.ReadAll on the other hand, lets append() directly handle the growth of the buffer, which follows some more complex logic.

But we’ll hit a similar issue here: by using append(), a copy of the array is created.

In both cases we need approximately double the file size in allocated memory.

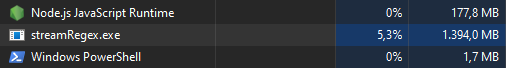

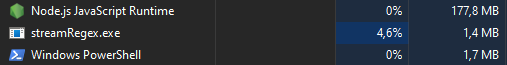

You can see in the screenshot the RAM usage for scanning a 500 MB file.

Using io.Copy with a bytes.Buffer and manually buffer.Grow(n)ing the buffer to the file’s size esures that no unforseen extensions/copying of the underlying slice happen.

That way you can keep the memory footprint as low as possible (RAM usage ≈ file size).

Due to all the copying, it should be clear that with the existing solution scanning files via regex requires at least the full file’s size in memory in order to process it. As shown above, the used memory can even be a lot higher, depending on how often the arrays are copied and how the garbage collector is feeling today.

A quick internet search revealed that I wasn’t the only one searching for a regex streaming solution to solve the memory exhaustion issue.

Because it scans all files on a system regardless of their size, I didn’t want to read full files contents into a

[]byte.

Since I could not find any existing solutions, I decided to give it a shot and create a library for that.

Developing a solution

I already knew that Go has really neat streaming interfaces - mainly io.Reader, io.Writer and all sorts of variants with even more features, that make working with streams an ease. Opening a file returns a struct that implements the io.Reader interface.

So I thought it would be incredibly easy to simply stream the file to the regex engine, but that was harder than I initially thought. The official regex module (regexp) only offers three methods that even take a stream as input. Those are:

- MatchReader(r io.RuneReader) bool

- FindReaderIndex(r io.RuneReader) (loc []int)

- FindReaderSubmatchIndex(r io.RuneReader) []int

It is important to note that these require an io.RuneReader to function. Since we read regular files, there is no RuneReader available to us by default. Also these methods don’t return the matches themselves but rather locations of the matches in the underlying stream.

Not the optimal point to get started, but not too bad either. So I set out to create my own reader that is capable of handling regex matching for streams. Introducing: rexamine

Implementation

The FindReaderIndex method looks very promising.

It takes a RuneReader and returns at first match with a slice containing the start and end indices.

Obviously, we need some sort of buffer in order to extract the matches based on the indices.

This already reveals a weakness of any stream based regex-reader.

If we wanted to support regular expressions matching arbitrary lengths (+/*/{3,} quantifiers), our buffer must store the whole file in the worst case.

Otherwise, a match might exceed the buffer size.

My use cases usually revolve around matching up to ~120 characters per match. That’s why I decided to limit the maximum match size by setting the default buffer size to 4 KB. If the length of a match exceeds the buffer size, the library will return an error. The buffer size can be easily changed.

Also, instead of using a single buffer, we use two. One to handle all the reading and writing operations between the source stream and the target stream (the regex package) and another one to always keep at least an entire buffer of previously read bytes to extract matches from.

Go offers a great buffered io module called bufio. While this package certainly helped me a lot to realize the implementation of buffered reading and writing, I couldn’t just use it out of the box. We need access to the underlying data structure in order to extract the exact match from the buffer.

At the core of rexamine is the RegexReader struct.

type RegexReader struct {

rd io.Reader

buf []byte

prevBuf []byte

pattern *regexp.Regexp

sourceReadBytes int // Total number of bytes read from the underlying reader rd

readBytes int // Total number of bytes read from this reader

prevReadBytes int // Total number of bytes read from this reader after the previous regex match

err error

r, w int // buf read and write positions

}

In this struct we store the source reader, two buffers, the regex pattern, three attributes regarding the amount of read bytes, an error and two pointers for the read and write positions within our buffer.

There are two constructors defined in the package.

func NewRegexReader(r io.Reader, pattern *regexp.Regexp) *RegexReader

func NewRegexReaderSize(r io.Reader, pattern *regexp.Regexp, size int) *RegexReader

The NewRegexReaderSize constructor allows for a configuration of the used buffer size (in bytes).

Since we need to implement the io.RuneReader interface for the regex package to read from, we’ll add a function called ReadRune.

That function is called by the regex package in order to scan through the stream.

func (m *RegexReader) ReadRune() (r rune, size int, err error)

Next, there should be functions to start scanning for matches in the stream.

func (m *RegexReader) FindAllMatches() ([]string, error)

func (m *RegexReader) FindAllMatchesAsync(deliver func(string)) error

FindAllMatches just blocks until all data is read and eventually returns with the matches and an error if any occurred.

Internally it just runs FindAllMatchesAsync which helps to process the matches as they are found.

Performance

The following benchmarks show that rexamine is about 5-7% slower than reading all the file’s content into memory and searching it with regex all at once. On the other hand, it uses only about 19 KB of memory.

Preparation

For the benchmark, we need to generate some binary and text files (haystack) in order to compare the different approaches. To do so, we used the following method:

Binary file:

dd if=/dev/urandom bs=100M count=1 iflag=fullblock of=sample.bin

Text file:

dd if=/dev/urandom iflag=fullblock | base64 -w 0 | head -c 100M > sample.txt

To insert some data (needle), we can later try to find with rexamine, we can use this:

echo -n "MyData" | dd bs=1 seek=1000 of=sample.txt

echo -n "MyData" | dd bs=1 seek=10000 of=sample.txt

echo -n "MyData" | dd bs=1 seek=100000 of=sample.txt

After that we only need to compile the four test binaries.

go build ./cmd/iocopy

go build ./cmd/iocreadall

go build ./cmd/rexamine

go build ./cmd/rexaminewriter

hyperfine

With the generated files in place we can now run rexamine on these files and compare different approaches. To do this efficiently, we can utilize hyperfine.

rexamine> hyperfine -w 2 -r 6 'iocopy.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex "..."' 'ioreadall.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex "..."' 'rexamine.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex "..."' 'rexaminewriter.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex "..."'

Benchmark 1: iocopy.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex [\w\-+\.%]+@[\w-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,24}

Time (mean ± σ): 8.045 s ± 0.279 s [User: 2.852 s, System: 0.049 s]

Range (min … max): 7.887 s … 8.612 s 6 runs

Benchmark 2: ioreadall.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex [\w\-+\.%]+@[\w-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,24}

Time (mean ± σ): 8.085 s ± 0.042 s [User: 3.263 s, System: 0.042 s]

Range (min … max): 8.023 s … 8.135 s 6 runs

Benchmark 3: rexamine.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex [\w\-+\.%]+@[\w-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,24}

Time (mean ± σ): 8.630 s ± 0.083 s [User: 3.729 s, System: 0.104 s]

Range (min … max): 8.572 s … 8.753 s 6 runs

Benchmark 4: rexaminewriter.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex [\w\-+\.%]+@[\w-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,24}

Time (mean ± σ): 8.601 s ± 0.041 s [User: 1.391 s, System: 0.062 s]

Range (min … max): 8.551 s … 8.669 s 6 runs

Summary

iocopy.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex [\w\-+\.%]+@[\w-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,24} ran

1.00 ± 0.04 times faster than ioreadall.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex [\w\-+\.%]+@[\w-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,24}

1.07 ± 0.04 times faster than rexamine.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex [\w\-+\.%]+@[\w-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,24}

1.07 ± 0.04 times faster than rexaminewriter.exe -file 500mb.txt -regex [\w\-+\.%]+@[\w-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,24}

Memory footprint

Since rexamine was specifically developed to decrease the memory footprint, the used memory is much more important than execution speed. We can use Go’s benchmarking tooling to get data on memory usage.

rexamine> go test -bench=./pkg/streamregex -benchmem -run=^$ -bench ^Benchmark.+$ -count 5

cpu: AMD Ryzen 9 7900 12-Core Processor

BenchmarkIOCopy-24 1 1618671100 ns/op 268449152 B/op 76 allocs/op

BenchmarkIOReadAll-24 1 1570844100 ns/op 615242440 B/op 106 allocs/op

BenchmarkRexamine-24 1 1751799700 ns/op 19464 B/op 58 allocs/op

BenchmarkRexamineWriter-24 1 1735913500 ns/op 53440 B/op 68 allocs/op

io.ReadAll needs by far the most memory allocations. For a 100 MB file, it allocates (and frees) more than 600 MB.

io.Copy requires less than that, but still around 270 MB.

rexamine completely crushes it with only 19 KB of allocated memory.

In total the whole used RAM for the rexamine application is about 2MB.

Obviously, rexamine is just a proof of concept. It is not thoroughly tested (yet?) and it is a bit slower than scanning all of the file in memory. But it provides a good basis to start off from. Give it a try and please provide me with feedback.

Cheers.